Five years on from his first trip to the Caspian, Rory Moore returned to Azerbaijan to find signs of hope for some of the largest and rarest remaining aquatic behemoths on the planet.

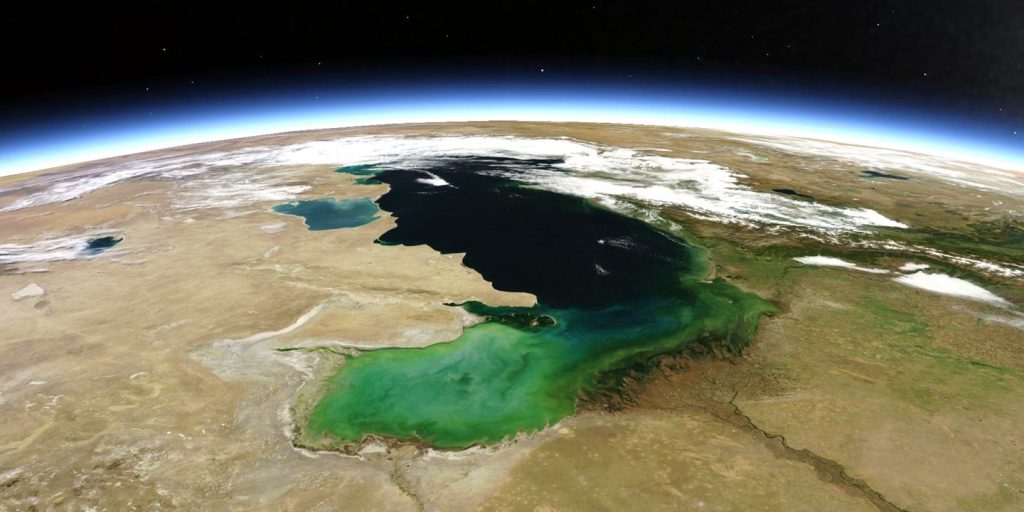

The Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland body of water, sits on enough natural gas to fuel the UK at its current consumption for 32 million years. A further 48 billion barrels of oil lie untapped under the seabed. As a marine biologist working in the region, I often wonder how the fragile Caspian Sea marine environment, with its endemic species of sturgeon, salmon, seal, kutum, kilka anchovy and lamprey, will survive, living on top of such an economically valuable resource. And then it gets even scarier. As these hydrocarbons are pumped to the surface and burned, CO2 is released into the atmosphere, the planet gets warmer and fresh water becomes scarcer in this region, leading to the construction of river dams to control water flow. These very dams prevent many of these rare, migratory species from reaching their upper-river spawning grounds. As the northern Caspian sea-ice melts, endangered Caspian seals lose their essential birthing ice-fields. At a worrying time in history for the world’s oceans, the Caspian Sea faces more threats than most.

This is what I was thinking about as the plane swooped over Azerbaijan’s gas fields and the bright lights of Baku, landing on an arid-looking peninsula. I was greeted by my colleague and friend Surkhay who runs IDEA, a local NGO focused on protecting the Caspian environment. We headed south on a five-hour drive towards the Iranian border. As the sun rose, Azerbaijan came to life all around us. We sped past new fields of solar panels and wind turbines – a renewable energy industry that has grown eight-fold, allowing Azerbaijan to export clean energy for the first time. Then there were the trees. Not the old forests that are found in the north and south of the country that are home to leopards, bears, wolves and bison, but new plantations amid the arid plains that stretch from the eastern coastline to the mountains in the west. Surkhay informed me that Azerbaijan had just planted 650,000 trees in one day to commemorate the great Persian poet and thinker Imadeddin Nasimi. This was no monoculture. A rich diversity of species had been planted: Khan’s plane tree, eldar, cypress, acacia, ash, elm, poplar, alder, willow, oleaster, wild pistachio, catalpa, olive, fig, peach, plum, apple, pomegranate, lime and catalpa (a deciduous tree, sole food for the catalpa sphynx moth).

As we crossed the great Kura river, a muddy artery that flows for 1,500 km from its source in Turkey, through Georgia, Azerbaijan and into the Caspian Sea, I was struck by the disappearance of the gillnets. When I first visited the region in 2015, I was appalled to see the amount of nylon nets that lay across the river, designed to entangle the gills of sturgeon, salmon and other anadromous fish as they made their way up the Kura river to lay their eggs. Two years earlier, Blue Marine Foundation (BLUE) and IDEA had convinced the government to ban the use of these deadly nets and it had worked. They were gone and that meant the fish could migrate!

BLUE’s conservation plan was simple in theory, but far from easy to pull off. We were building on a Caspian-wide ban on sturgeon fishing and protection of other endangered species like salmon and kutum. If we could open up the rivers for migration, protect certain areas from fishing, restore spawning habitats upstream and develop alternative livelihoods, specifically sustainable fish farming, we could give Caspian marine life a chance to recover.

We pressed on towards our destination, Ghizilagac, a vast wetland and the site of the first ever marine protected area (MPA) in the Caspian Sea. Two years ago, I had identified this site as crucial for juvenile critically endangered sturgeon as they adjusted their systems from fresh to saline water. The shallow waters surrounding the wetland are also home to spawning kutum, Caspian salmon and an incredible diversity of marine life.

The Ghizilagac MPA, only designated a few months earlier, was coming along well. There was a brand-new tourist information centre, informing visitors about flora and fauna in the park. This would be the first time that eco-tourism was permitted in the area since it was closed off in the 1920s, resulting in poachers taking advantage of the returning birds and fish. New patrol boats were now moored in the channels that meandered through the thick reed beds and out into the MPA. Rangers were undertaking extensive training programmes and newly erected signs made it clear that hunting and fishing were strictly banned.

When the MPA was being established, I had convinced Sylvia Earle’s team at Mission Blue to designate the area as a ‘Hope Spot’ – a special place that is critical to the health of the ocean (or in this case, a vast sea). Hope Spots recognise, empower and support and communities around the world in their efforts to protect the ocean. This was the first Hope Spot in the region and would bring international attention to the plight of the Caspian Sea.

Just north of the MPA and Hope Spot in the vast Kura delta, a new fish farm was being built specifically to rear various species of sturgeon for the marketplace. BLUE has been working with the team at Azerbaijan Fish Farms to identify alternative sources of protein to feed the precious fish. Masters students from the University of Stirling shipped over innovative diets from Scotland including insect protein, waste offal and plant additives to see if the sturgeon would accept an alternative to wild fish. The project is proving a success and a new production plant has been built to make the feed. The fish farm will provide the market with high-quality, sustainably produced fish and provide alternative employment opportunities for ex-poachers. There is even an education centre on the site to teach new skills to the community: aquaculture, marine biology, eco-tourism and environmental sciences. For every jar of caviar sold, the farmers will release juvenile sturgeon (fingerlings) into the MPA, bolstering the natural population.

As the sun set over the lower caucus mountain range we headed north back to Baku. Occasionally we passed old bathtubs on the side of the road. I asked Surkhay why they were there and he told me that fishermen would keep their catch alive in the tubs, fresh to sell to passing travellers. Makeshift market stands, brimming with pomegranates, honey, jams and wild herbs added dashes of colour to the otherwise plain landscape and the faint odour of burnt oil drew my gaze to the flaming platforms projecting from the sea.

I woke early the next morning and hailed a taxi to take me to the ‘Taza Bazaar’, one of the oldest street markets in Azerbaijan. The bazaar was renowned for its exotic wares. I had been fascinated with the bazaar since my first visit in 2015. It had been my first field trip for BLUE and I had been keen to impress. So keen, that I had ended up in a cold, eerie basement under the market faced with a mountain of frozen, illegally caught sturgeon and old fridges filled with caviar. It was a sobering scene which I will never forget. However, four years later, the market was different. The pickled walnuts and figs, the stacks of handmade cookware, the Soviet-era knickknacks were all still there, but the fish had all but gone. Just a few sturgeon lay on the countertops. Next to me a customer was purchasing a few kilos of prized beluga sturgeon meat and I asked him why there were so few fish. He told me that rules were stricter and the wild fish harder to buy. His fish had been farmed and he was paying a high price for it. Some carp and two massive catfish were the only other aquatic offerings that morning so I left the bazaar in slight bemusement – had the sturgeon really been protected or were there just no fish left at all?

I went back to the hotel and called an old friend, Zaur Salmanov. Zaur was a marine biologist and expert on sturgeon. He had learned how to breed sturgeon with my uncle in California, who himself was a leader in the field in the late 1980s. Together they had perfected diets for juvenile sturgeon. Zaur now ran the ecological side of Azerbaijan Fish Farms and the new fish feed processing plant. I met Zaur at a dark, old underground steakhouse and we sat together under the lights of Baku deliberating the future of endangered sturgeon and Caspian salmon. Zaur was in an upbeat mood. The sturgeon farm was nearing completion and his broodstock fish were soon to be introduced into the giant, oxygenated ponds. Thousands of baby sturgeon had been released into the wild and Zaur had heard reports of Caspian seals sighted for the first time in years near the MPA. I told him of my experience in the market and he wasn’t surprised. Yes, stricter rules to limit the black market of sturgeon products seemed to be working and new fish farms like his were providing more fish to meet local and regional demand. The gillnet ban had been a great success with patrol teams regularly removing and confiscating the illegal fishing gear. That was not all. Zaur had been speaking to fishermen who had recently been catching sturgeon far upriver. This meant only one thing; at least some fish were returning to find gravelly riverbeds to lay their eggs. We toasted this good news over a bottle of Azeri wine and said our goodbyes.

That night, I stayed up late watching BBC world news: Trump dead set on reversing any progress made in the fight against climate change, Extinction Rebellion filling the streets in protest, forest fires blazing in Australia, intensive Chilean salmon farms polluting Patagonia’s fjords, Spain overfishing tuna in the Indian Ocean and UK’s fishermen wondering what Brexit will mean for their livelihoods. What a time for a marine biologist to be alive, I thought, trying to restore fish populations in slowly warming, acidifying oceans and so many mouths to feed. Yet here, in the Caspian there was hope. In Azerbaijan, a country born from fossil fuels and fed by now endangered marine species, here was alternative energy production, innovative proteins, marine protection, fish adapting to new conditions in order to survive…yes, there was hope. It reminded me of what my uncle had once told me when I was younger: ‘Rory’ he said, ‘just go and give those sturgeon a chance. They are strong, resilient, patient beasts and have been living on this planet for about a hundred million years longer than us. Just give them a chance.’ And that is what we were doing – giving a fish a chance against all odds. And perhaps it was working….