Why are British cod in trouble?

Since Blue Marine launched a Parliamentary petition to #BringBackBritishCod – supported by many other groups – there have been many questions on social media about the state of cod stocks. We have gathered these together and tried to answer them below.

Why is British cod so important?

There are multiple reasons to look after and restore our domestic stocks of cod, a significant fish in UK diets: for the good of a wild species in decline; for food security in times of adversity such as these; for the good of the fishing industry, fish and chip shops and other industries that depend on them; and for the benefit of the marine environment because excessive pressure on cod puts pressure on other species.

What does the science say?

There are five distinct cod populations (sometimes called stocks) that occupy UK waters; the Celtic Sea, Irish Sea, West of Scotland, Rockall, and North Sea populations. Each year the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) carries out a stock assessment and provides advice on what level of catch would be sustainable[1].

The scientific assessments of cod in UK waters show that cod populations in the UK have plummeted in recent decades. The primary driver for this decline is overfishing. The figures presented by ICES are stark:

- West of Scotland cod stock has declined by 92% since 1981

- Celtic Sea cod has declined by 88% since 1980

- Irish Sea cod has declined by 89% since 1960

- North Sea cod has declined by 59% since 1963

In all these instances the level of fishing pressure that governments have allowed has been at a level that makes population decline inevitable. Once the stock has collapsed fishing has been allowed at such a high level that recovery is impossible. In the North Sea a plan was put in place to recover cod and it did begin to work before fishing pressure was again ramped up and the stock declined again.

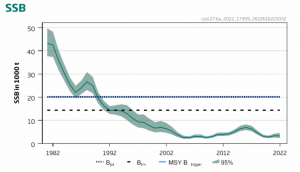

ICES graph showing West of Scotland cod stock decline since the 1980s. SSB stands for “spawning stock biomass” – the combined weight of all individuals in a fish stock that have reached sexual maturity and are capable of reproducing.

How do you define a stock that is at risk of collapse?

Scientists define various reference points within a fish population. The lowest one is called biomass limit reference point or “Blim.” Any stock below this is considered at risk of collapse. Sadly, the cod stocks in the North Sea, Irish Sea, Celtic Sea and off the West of Scotland are all below this point.

Could the science be wrong?

Some fishermen have suggested that the official science on cod is wrong and there are huge numbers of fish out there on the grounds. There are many reasons why in some areas there appear to be an abundance of fish, but those accounts are not necessarily a true representation of the entire stock.

ICES advice shows us that catches from the North Sea stock are at very low levels compared to the past. Some fishing industry groups have said that their fleets are catching huge quantities of cod but that it is having to be discarded due to low quota. We would point out that discarding of cod is illegal and these discards are not being recorded if that is the case. We would also note that for catches to be at anything like historical levels then the number of cod being discarded illegally must be extremely high.

Cod stocks, like any population are dynamic, and there will be good years for recruitment and bad years. Cod reach sexual maturity at different ages in different stocks with some reaching sexual maturity at two to four years (40 cm) and others at six to nine years (60 cm). We cannot rely on one or two years‘ observations that cod appear to be higher in number to justify continued over-fishing.

The Fisheries Act requires that “the management of fish and aquaculture activities is based on the best available scientific advice”. The assessments by ICES are clear that the UK’s cod populations are very low and, in most areas, have been declining over a period of many years.

Who is ICES?

ICES is an intergovernmental marine science organisation made up of experts that are asked to provide stock assessments and catch advice. It is fully independent and provides the best available scientific advice. The network includes scientists from many countries, including the UK.

Why are you using different dates for each cod stock?

In calculating the changes in population of each stock we have used the earliest year in each assessment – that is why we haven’t used the same year for each. We did this to avoid any risk of “cherry picking” data. For example, when calculating the change in North Sea cod we used 1963 as the starting point as this is the first year in the ICES assessments – this was not the year of the highest North Sea cod population. We have taken this approach of using the first available year rather than “picking a year” for each stock.

Is climate change responsible for the collapse of cod?

No. There is evidence that warming oceans will have significant impact on many fish species[2] but also that fishing pressure also remains a huge factor in the abundance and range of marine life[3]. We share concerns about the impact of climate change on marine life, including cod, but this does not mean that it is acceptable for government to simply allow rampant overfishing and then blame the resulting stock crashes on climate change. In the face of increased uncertainty from climate change the responsible management decision is to be more precautionary – not simply to overfish more. This approach is enshrined in the UK Fisheries Act which explicitly includes a precautionary objective and a climate change objective.

We also know that when fishing pressure has been reduced in the past, we have seen the beginnings of recovery – this shows that fishing pressure still has a huge impact on stock health. If climate change was the sole cause of cod decline, then reducing fishing pressure wouldn’t make a difference – and it does. The North Sea stock, as the biggest cod stock, is the one that has attracted most attention. Previously a cod recovery plan was introduced in the North Sea, a plan that begun to have an impact and the cod population begun to recover. Unfortunately, decisions were then made that reversed the initial successes of the recovery plan and the stock subsequently declined again as fishing pressure was increased above the level that would allow the population to rebound.

How are cod stocks managed?

Every year an overall catch limit is set for each cod stock. This is the same approach used for many other species such as haddock, whiting or plaice. The catch limit is negotiated between the UK and the EU (as these cod populations inhabit both UK and EU waters). For the North Sea cod population the negotiation includes Norway. The various countries are supposed to agree to a catch limit that is in line with the scientific advice provided by the ICES. The total catch level should be set at a level that does not exceed this scientific advice, but unfortunately, the EU and UK have continuously failed to do so.

What is our Parliamentary petition asking for?

Our petition’s ask is a very simple one – we want the UK government to stop allowing overfishing and to follow its own policies and its own laws. Last year 65 per cent of all the catch limits agreed between the UK and the EU for fish stocks in their waters were set above the scientific advice – this included the catch limits for cod. That is unacceptable.

The Fisheries Act requires the government to restore or maintain fish populations above healthy levels – the same requirement the EU has under the Common Fisheries Policy. This requirement is laid out in other UK laws and is central to a number of international commitments – including UN sustainable Development Goal 14. In fact, under many of these laws and commitments the British government and the EU were required to end overfishing by 2020. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea was signed on 10th December 1982 – that will be thirty years to the day when the fisheries negotiations are finalised this year. On that day it will be exactly three decades since the requirement under UNCLOS to fish sustainably was put in place.

[1] Sustainability is defined as achieving the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) and meeting the precautionary requirement that both the EU and the UK include in their legislation. MSY is the requirement under EU and UK law and policy not Blue Marine Foundation’s definition.

[2] Avaria-Llautureo, J., Venditti, C., Rivadeneira, M.M. et al. Historical warming consistently decreased size, dispersal and speciation rate of fish. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 787–793 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01123-5

[3] Georg H. Engelhard (1), Tina K. Kerby (1,2), William W.L. Cheung (3), and John K. Pinnegar (1) (1) Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), Lowestoft, UK; (2) University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK; (3) University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.